Recruiting people for design research can be a beast. Anyone will tell you. It’s always a challenge to make sure you’re getting people in the right demographic, with the right level of technological comfort, who have the specific behavior or mindset you’re searching for – and who happen to be available during the time you’re hoping to meet with them. Lately I’ve been hearing some folks at healthcare start-ups say they don’t speak with patients or include them during their design process – because they don’t know how or where to find patients.

I’d like to break this down. If you’re involved in creating any product for which patients are a stakeholder, here’s 1) why you need to include patients in your process, 2) what you risk by not including patients, 3) some creative ways to recruit patients, and 4) an important public service announcement about paying patients for their time.

—————

Why you need to include patients in your process

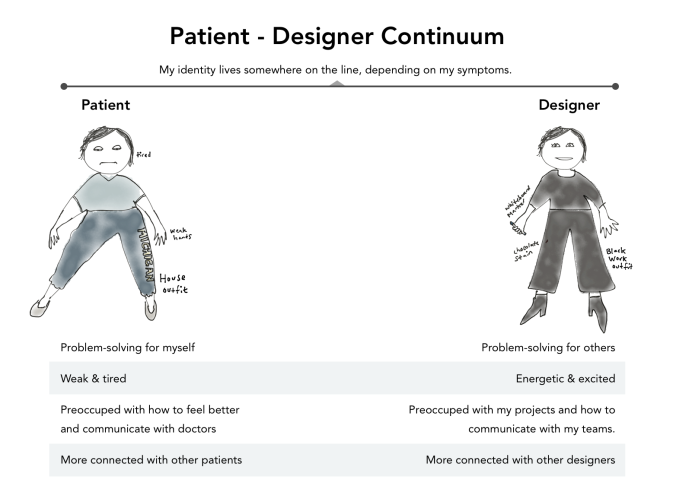

As a ‘User Experience Designer,’ it’s my job to make sure I have a full understanding of my end users and their context. That’s true for any designer, anywhere – from the industrial designer creating bic pens (can you imagine? who is this person?) to the fashion designer creating a sassy pant suit, to someone creating a mobile app for diabetics. We designers need a good understanding of our users before we start designing, and we need to get continuous feedback throughout the design process to make sure the design direction meets users’ expectations and solves real problems. It’s part of our process; it’s how we make things that people like and want to use. My research most often involves interviewing people, observing them in their environment, and creating product prototypes for them to interact with and react to.

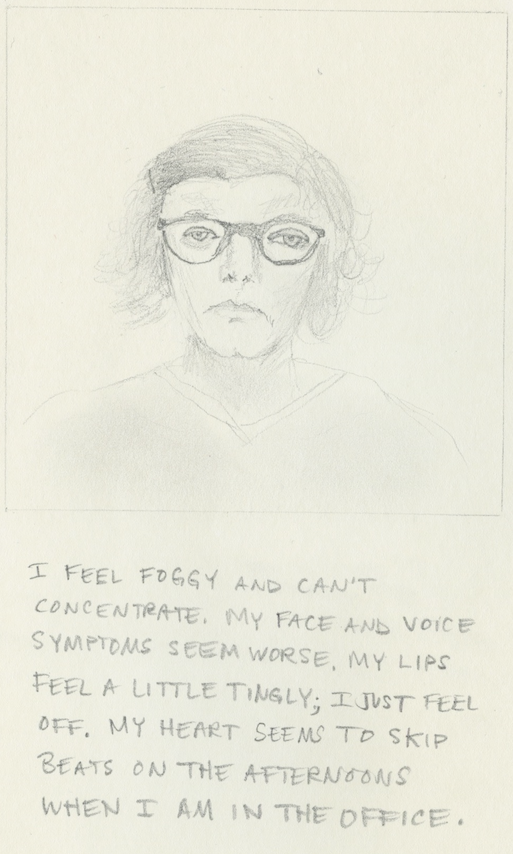

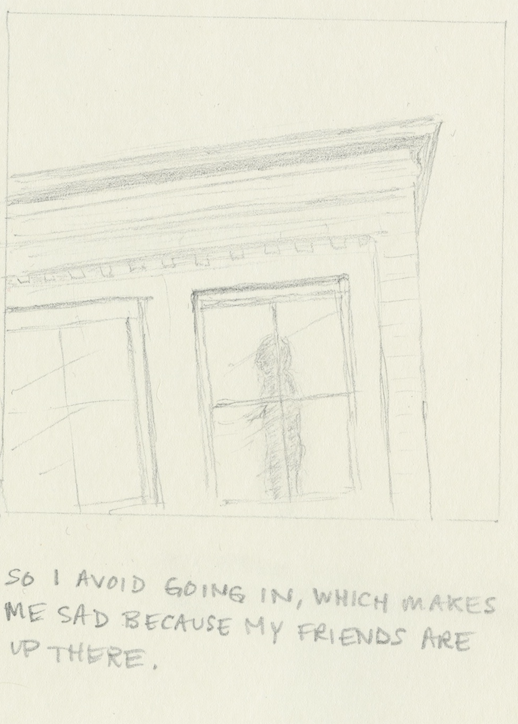

I’ve worked pretty much exclusively in healthcare for the past couple of years, and I have found researching with and designing for patients an especially rewarding and emotional experience. Patients are always up-ending my assumptions about how they manage their condition, what their days are like, and how they’re feeling. Their stories are often private, sometimes painful, and sometimes hard to hear. I feel honored with their stories and perspective. While I always find ways to communicate design findings to my team, I also carry their words and emotions inside me, in my heart, throughout the course of the project and even into subsequent work.

Without fail, the insights that we gain from patient research have prompted my teams to make vital changes – to the core product concept, to language and terminology, or to the look and feel of the product.

—————

What you risk by not including patients

If you intend for patients to use your product in ANY way, you need to include them in your design process. If your intended user will interact with patients during the course of using your product (think provider or office staff), you need to include patients in your design process. If you do not have a full understanding of your patient users or stakeholders, you risk building the wrong product, putting emphasis on the wrong features, and generally creating a sub-par product that no one will want to use.

Question: What if I don’t have time or money to include patients in my product development process?

Answer: if you have time and budget to create your product, you surely have time to make sure you’re building the right thing. Researching with users can be a ‘fast and light’ process – it can be as lightweight or in-depth as you want to make it.

Question: What if patients are my intended end users, but they aren’t my target ‘client’ or aren’t otherwise paying for my product? Why should I spend the energy to understand their perspective?

Answer: If you sell a product intended for patients, and patients don’t want to use it because it isn’t well-designed for them, your client won’t like you and they’ll find someone with a better product. A shame spiral will ensue. You will end up living in a van…down by the river.

If you don’t include patients in the design of your healthcare product, you will end up living in a van down by the river

—————

Some creative ways to recruit patients

Now that we are on the same page about the importance of involving patients in design, let’s talk about how you can find them. Before you start looking, though, you’ll want to make sure you know which kinds of patients you need to talk with; outline the characteristics you’re looking for, and create a screener (i.e., a list of questions that you can ask prospective participants to make sure you’re getting the right breakdown of folks.) That said, here are some ideas for finding patients:

1. Post flyers at healthcare clinics and institutions

I have done this with some surprising success. I created flyers last year for a research project I was doing; I was looking for Android users with diabetes who were willing to speak with me for 30 minutes in exchange for a gift card. I distributed the flyers at a diabetes clinic, after calling and getting support from a nurse who worked there; over the next few months, I got at least 12 responses from it. You will always need to get permission before putting up these kinds of flyers, or else they’ll be taken right down. Big hospitals usually have lots of rules about this kind of thing. Smaller clinics might be easier. I gained an especially awesome ally through flyering: I connected with a person who I call the ‘Don’ of the local diabetes mafia – a very productive contact who passed my name along to her underground diabetes community and got me a number of interview subjects. See also, ‘influencers,’ point #2.

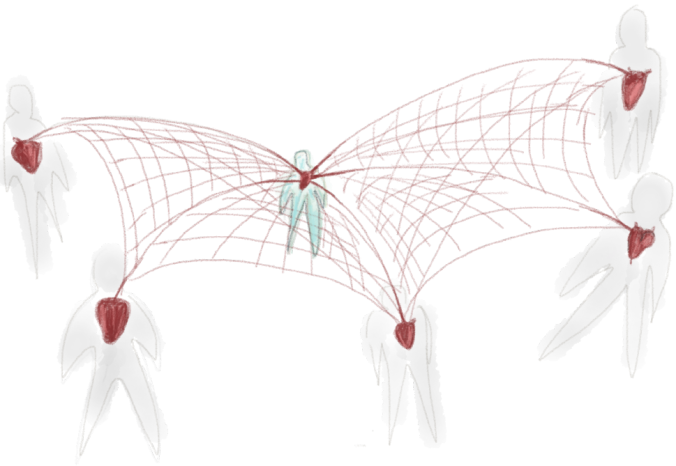

2. Find the ‘influencers’

This one is exciting. If you can connect with a key patient leader, one that the rest of the community looks up to, a whole world of patients can be opened up to you. This happened with me and the diabetes mafia – once I met the Don of the mafia, I was flush with participants for my project. It was amazing. Places to find influencers: twitter, patient blogs, patient communities. Look for patients who are speaking out openly about their condition, perhaps at conferences or events. Get creative and find them however you can.

3. Show up at support groups

This sounds a little creepy, but when handled with finesse and discretion this can be a good way to get potential participants. If you decide to try reaching out to people via a support group, I recommend that you contact the support group leader as your first step. Explain what you are doing and who you are working with, tell them that you are trying to help create a better healthcare experience for patients who have [x condition], explain that you are paying patients for their time, and ask if it is ok if you come to the beginning of a meeting to give a quick overview and pass out flyers. They may say yes – if so, that is great. If they say no, ask if they would be willing to circulate your flyer among group members.

If and when you go: show up a little early and try to chat 1-on-1 with a few people before the start of the session. Prepare some small cards or hand-outs about your project. Give your spiel. Make clear that you are not a patient (of course, unless you are,) and then graciously leave before things get awkward.

4. Connect with online patient communities, including twitter

There are multiple online communities for almost any condition you could possibly think of. These communities themselves can be a wonderful mine of patient opinions, emotions, fears, needs, goals, etc. Assuming you want to talk to actual people and ask them questions, here are a few tips. First, try reaching out to the community leader before joining any private disease community. You don’t want to be a weird lurker and you don’t want to misrepresent yourself as a patient when you actually aren’t (unless, of course, you are – in which case, go wild.) Ask if you or they could start a discussion thread about the opportunity to speak with you. This is especially helpful if you’re up for doing remote research with people – like over skype or google hangouts, or even phone.

You’ll also find a hearty discussion on twitter for most conditions. Find out what hashtag the condition is using, and tweet out your opportunity using that hash tag. In this case, it’d be good to create a basic webpage with information about your study and either a form for interested folks to fill out or a phone number for them to call. This strategy can be good for remote research, but maybe not so good if you need people in your immediate geographic area.

5. Reach out to ‘friends and family’

Depending on how specific your recruiting is, your social network may be a great place to pick up a few additional participants. Send an e-mail to everyone you know who might be a good lead or who may be able to connect you to others. If just one of your people forwards the email to a few friends, you might gain a few participants right there. Be careful about always relying on the friends and family connections – you don’t want to be using the same little pool of people for all of your research projects.

—————

An important public service announcement about paying patients for their time

Pay patients for their time. It is absolutely standard practice to pay any user research participants for their time. Patients are no different. If you are getting paid for your project, you owe it to patients to pay them for their time; they are helping you create a better product, get better insights, and basically create better value for your client or company. They have a lot of medical expenses. Their time is money, just like yours. Pay them! Pay them at a competitive rate!

(If you are working on a passion project and are not getting paid by anyone, that might be a different story. But if there is a stream of cash involved, funnel some of that cash to patients.)

—————

There’s so much more to talk about, but these are at least a few ideas to get you started. Please post any other thoughts you have or strategies for recruiting patients – I’d love to hear ’em.